Mathew Knowles Talks Beyonce, Racism, Getting Vaxxed

- ssanders1208

- Oct 29, 2021

- 14 min read

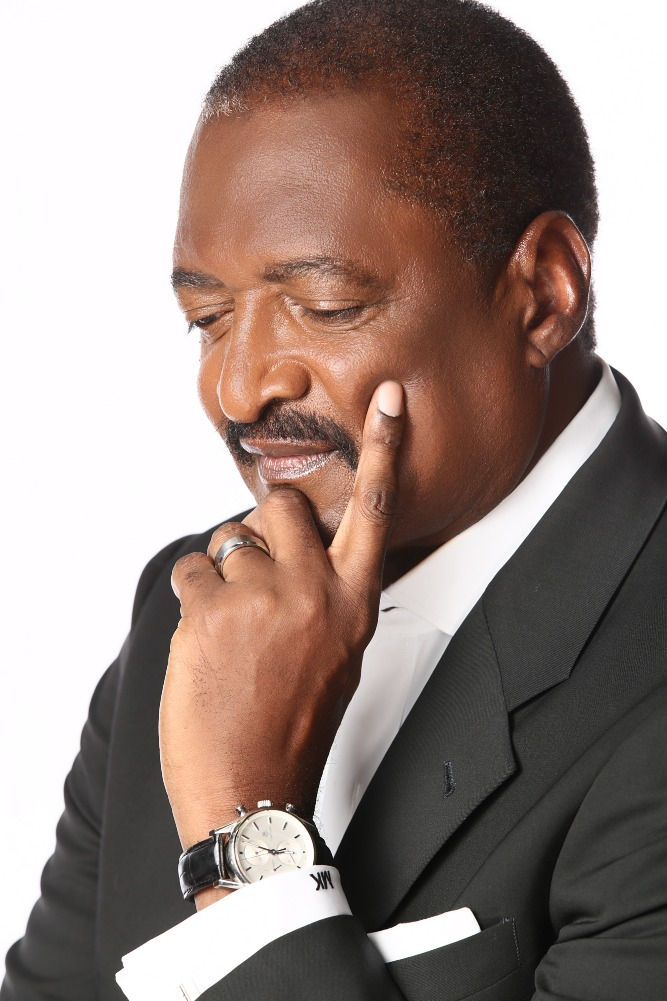

Music Executive, artist manager, entrepreneur, activist, lecturer, author and cancer survivor, Mathew Knowles brought the world multiplatinum selling girl group Destiny’s Child, singer-songwriter Solange, and multi-hyphenate megastar Beyonce. He’s worked with music legends, Chaka Kahn, the O’Jays, Earth and Wind & Fire, and sold more than 450 million albums, worldwide.

A devoted academic who earned his MBA in Strategic Planning and Organizational Culture and his Ph.D. in Business Administration, Knowles currently mentors and teaches emerging entrepreneurs and artists with courses like his most recent, The Music Industry in the Digital Age, through Point Blank Music School where he holds a professorship; Knowles additionally holds professorships at University of Houston, Prairie View A&M University, and The Art Institute.

Most urgently, Mathew Knowles is on a mission to help get more Americans in underserved communities vaccinated against Covid-19 alongside the National Minority Health Association’s Flex For Checks program, which can be learned about at thenmha.org and flexforchecks.com.

Allison Kugel: What is the National Minority Health Association, and how did you get involved with their Flex for Checks initiative?

Mathew Knowles: The National Minority Health Association is working with brown and Black communities on various health initiatives. For example, when we look at Black men and we look at the percentage of Black men in America, we lead in mortalities in every category, Allison, except for breast cancer and suicide. Black women lead in mortality rates for breast cancer. Why is that? Because of a lack of awareness in our communities. It’s about lack of early detection. The National Minority Health Association’s specific program, Flex For Checks, is about increasing awareness about getting vaccinated [against COVID-19]. You register, you get a shot, and once you’ve proven that you’ve gotten the vaccination, you then receive $50.

Allison Kugel: That is once you’ve gotten your complete vaccination, meaning two shots, with the exception of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, which is a single shot?

Mathew Knowles: Every time you get a shot, regardless of if it’s one, two, or the booster, you will receive $50.

Allison Kugel: At this point in time, you can pretty much walk into any CVS, Walgreens, Rite Aid, any clinic or vaccination site, and get your COVID-19 vaccine. You don’t have to pay for the vaccine, it’s free for all Americans, and readily available. So, when you say “lack of access” or “underserved communities,” is it more about getting people the correct information regarding the vaccine?

Mathew Knowles: It’s both. We are almost there with 70% of the U.S. [vaccinated], but there is still that 30% [that is not vaccinated]. So, what do we have to do to convince and incentivize that 30%, of which there is a high minority rate? We are giving a financial incentive. I know it sounds sort of absurd that I have to give you a financial incentive to save your life, but if that is what it takes, then that is what the National Minority Health Association is willing to do, with a grant they have received. It’s to incentivize people to go and get vaccinated.

Allison Kugel: Is there, in your opinion, a skepticism of government and a skepticism of the medical establishment, among many people of color?

Mathew Knowles: There is, and I happen to have this sheet that I pulled up which talks about the myths. One of the myths is, “the vaccine hasn’t been tested on people like me,” meaning people of color. The truth is the clinical trials for all three vaccines have taken all kinds of diversity into consideration. Pfizer: 30% people of color. Moderna: 37%. Johnson & Johnson: 35%. So that myth is busted. And there is a myth about the side effects of getting the COVID-19 vaccine. The truth is, while there are some mild side effects, and I got the Moderna vaccine as well as the booster, and did have soreness in my arm for two days, but the risk/reward of me having a sore arm versus having a ventilator down my throat. Let me weigh that out.

Allison Kugel: I think some aspect of vaccine hesitancy is, simply, fear of the unknown. People might be thinking, “What kind of side effects will I get?”

Mathew Knowles: I have a cup of tea in front of me right now. I’m going to drink it. I have no idea what all of the ingredients are in this tea. I have no idea if this cup will give me any side effects. That is true for so much of the food we eat, medications we take, and so forth. We have to put this into the proper perspective. We never really truly know every ingredient we put into our bodies. But we have to have trust in the science and in the research. I haven’t heard anybody say what I’m about to say, but I think a lot of people haven’t gotten the vaccine because of a fear of needles. There are a lot of people that are traumatized by a needle, and nobody is talking about that.

Allison Kugel: You might be right. It’s a common phobia. I actually made the woman who gave me the vaccine hold my hand, because I was such a baby (laugh).

Mathew Knowles: Well, I mean, it’s normal, but no one is really saying that. I really truly believe that a lot of this is just a phobia of getting a needle in the arm.

Allison Kugel: Which, by the way, you really don’t even feel. It’s just two seconds. You blink and it’s over.

Mathew Knowles: I didn’t even know. The doctor was talking to me and the next thing I knew I’m asking, “When are you going to give me the shot?” He said, “I already did.” I said, “Wait, what (laugh)?!”

Allison Kugel: Sadly, we just recently lost Colin Powell to complications from COVID-19. Something came out in the news that was confusing to many people. His loved ones stated the following, “We want people to know that he was completely vaccinated.” That statement then gave rise to more skepticism of, “See? He was vaccinated and he died from COVID complications.” But it is important to note that he had been battling a cancer of the blood, which significantly compromised his immune system, and it also made the vaccine less effective.

Mathew Knowles: People will use that as a reason not to get [the vaccine]. However, this is based on the information in the last 24 hours that I have listened to and read: he had a compromised immune system and [allegedly] he had not gotten the booster shot yet, is what I also read. Again, this is not necessarily all accurate, I’m just citing what I’ve read and heard. I have a compromised immune system, and I understand that getting a COVID shot doesn’t necessarily 100% mean that I’m not going to get COVID. What it’s supposed to do is not have me in the hospital with a ventilator down my throat, hopefully. For that reason, I was one of the first to get it, and I think it’s very unfortunate, but we have to understand there were other underlying conditions.

Allison Kugel: How do people get the financial compensation after they have gotten vaccinated? How does the process work?

Mathew Knowles: You can register for the program by calling 877-770-NMHA, or you can go to flexforchecks.com. Registering is the first step. Then you get the shot at one of the many locations in your community, and we identify those for you. You then upload proof of your vaccination to your Flex For Checks profile. Once you upload your proof of vaccination, we will automatically mail you a check. It’s that easy.

Allison Kugel: Perfect. I’d like to go into some of your personal history. You grew up in Alabama in the 1950s and 1960s. I would imagine you lived through your fair share of racial discrimination. What was your first-hand experience?

Mathew Knowles: I’ve written five books, and one of those is Racism from the Eyes of a Child. My mother went to high school in a small town in Alabama, with Coretta Scott King. Also in that class was Andrew Young’s wife. My mother then moved to a larger town in Alabama, and she took up the torch of desegregation. Imagine, I was born in 1952, so from 1958 to 1972 I went to all white schools. Think about that.

Allison Kugel: All white schools, meaning you were in the significant minority…

Mathew Knowles: In my junior high school, there were 6 Blacks and 1,000 Whites. In my high school, there were maybe 20 Blacks and 3,000 whites. The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga had 14,000 whites and maybe 50 Blacks. Then I transferred to an HBCU, Fisk University in Nashville, which was my first experience in a Black educational environment. I was one of the first [students] with desegregation. I had been beaten, I’ve been electrically prodded, I’ve been spit on, I’ve been humiliated, all sorts of trauma. I had to go to years of therapy to overcome it, no different than for a woman who has been sexually assaulted. Racial trauma is the same. It just doesn’t get the attention that it should. It’s unfortunate that a woman can speak of being sexually traumatized 30 or 40 years ago, but you can’t be Black and say that. Nobody cares.

Allison Kugel: Any recent stories regarding racial discrimination?

Mathew Knowles: I always love what Michelle Obama once said about President Obama. They asked her, “Are you frightened that your husband is going to get assassinated?” She said, “You know, my fear is that my husband could get shot by the police, pumping some gas.” The point she was making is that when you are Black there is no determination that says, “Hey, I’m the president,” you know? For example, with me, if you are in your neighborhood and you’re dressed normal, when you’re Black everyone doesn’t know who your daughter is, nor do they care. Just recently, I’m on a plane putting my bag up in first class. The flight attendant comes over and says, “I’m sorry, sir. You need to put your bags in the back, in coach.” I said, “Do you say that to all of your passengers?” She says, “Yes, I say that to all of my coach passengers.” I said, “So you just assume I’m flying coach, huh?” Those types of things still happen today.

Allison Kugel: How did you eventually make your way to Houston? And do you think the success that your daughters, Beyoncé and Solange, have had in the music industry, and the success you’ve had on the business side of the music industry, do you think that could have been possible had you stayed in Alabama? Or would there have been no ladder to climb up?

Mathew Knowles: It was more from my educational path, from getting a proper education. I was in Nashville, Tennessee and I chose Houston because of all the industry. At the time, you had affirmative action and you had quotas that these major oil companies and all the other companies that were successful because of the oil initiative in Houston, had to fulfill. So at that time in Houston, it was very easy being Black and getting a really good job. That is why I went to Houston, Texas from Nashville. I grew up in Gadsden, Alabama, where we had a Goodyear plant and we had a public steel plant, real blue collar. Chances are I would have ended up working at one of those types of facilities had I stayed in Gadsden. My parents had encouraged me and my vision was much broader than that, so I wanted to go and get the academic knowledge, and then I got 20 years of corporate experience.

Allison Kugel: You’re working in Corporate America for Xerox. What gave you the power of belief to make the leap from a stable corporate job to pursuing the music industry, with Destiny’s Child and Beyoncé, and then for Solange? Was it blind faith?

Mathew Knowles: I call that the “Jedi Mind Trick,” Allison. Unfortunately, that is the story that the media has painted and it’s not accurate. It’s not even close to being accurate. I worked at Xerox Corporation for ten years. Eight of those years I worked at Xerox Medical Systems. We sold diagnostic imaging for breast cancer detection. Because of my success, being the number one sales rep worldwide for three years in that division, I was able to then go with Phillips Medical Systems to sell CT and MRI scanners. After 6 years of having success, I had headhunters calling and I went to Johnson & Johnson as a neurosurgical specialist. Then because of managed care, I was told by a neurosurgeon that he couldn’t use my instruments because of the cost associated with them. It was a defining moment and I had to decide what career path I wanted. As a kid I did things like deejay for my parents, I was in a boy band, and I had this passionate love of music. There was this young man in Houston who had asked me a couple of times to manage him. The first artist that I got a major record deal for was not Beyoncé. It was not Solange. It was a rapper named Lil’ O. MCA records was the number one urban record label at the time with Puffy, Mary J. Blige, and Jodeci, so you see how inaccurate that story is?

Allison Kugel: You got your foot in the door with MCA Records, managing rapper Lil’ O, prior to launching Destiny’s Child. We’re busting apart the myth right now.

Mathew Knowles: Yes (laughs). I also went back to school, because I believe knowledge is power. For 15 years I’ve been a college educator, and so I went back to college and took three courses. I went to every seminar I could. I began to build every relationship that I could. You have to understand, skills are transferable. I was able to transfer my skill of being the top salesman in corporate America to the music industry.

Allison Kugel: That’s important. People may not realize that whatever their skillset is, that experience is transferable and can be used to pursue additional opportunities or careers.

Mathew Knowles: If you talk to anyone that worked at Xerox or Phillips and knew me, they would say, “I’m not surprised he was successful in the music industry.” Then, of course, I had this amazing talent to work with. Let’s not leave that out of the equation (laugh).

Allison Kugel: Yes, you did. I don’t know if anyone has ever asked you this before, but did Destiny’s Child, Beyoncé, Solange, or you for that matter, ever experience any racism within the music industry?

Mathew Knowles: Yes, absolutely. In the ‘90s, record labels had their urban division, or sometimes it was called the Black music division. There was segregation inside of these major record labels. Because I also managed white artists, I got to see all of the budgets. There was a great difference in a Black artist’s or “urban division’s” marketing budget from that of a white artist’s budget and the regular pop music division’s budget.

Allison Kugel: What is the best advice you have ever received?

Mathew Knowles: When you live your passion, you never work a day in your life. Find that thing that motivates and inspires you. Find what adds fuel to your excitement. That is the thing we should be working towards. Not what our parents want us to be, or what society wants us to be, or what our husbands or wives want us to be. It should be that thing inside of us that we are passionate about. Normally, that gives us success, not overnight success, but over time. If you follow your passion, every day you wake up you will be excited.

Allison Kugel: What do you think you came into this life to learn, and what do you think you came here to teach?

Mathew Knowles: It would be to educate and motivate people. I grew up poor, yet I never knew I was poor until I was in my mid 20s. My parents were such great parents that they never made me feel less fed than any other kid. I had wonderful parents that motivated me and supported me. I come from a family of entrepreneurs on both sides of my family, so I had that foundation. I have always wanted to educate and motivate people. That’s why I think I always did so well in sales and marketing, because I understood how to motivate and educate with knowledge. I love coming from a place of knowledge. I don’t shoot from the hip. My dad made $30 a day driving a produce truck and convinced the company he worked for to let him keep the truck. He would then go tear down old houses and he would sell all the copper and metals. He would buy old cars that were abandoned and sell all the parts. My mother was a maid and she made $3 a day. She convinced the white woman she worked for and the woman’s white girlfriends to give her all their hand-me-downs, and on the weekends, she would make these beautiful quilts with two of her own girlfriends. My parents made six to ten times more on their second jobs than they did on their day jobs, and so I watched that. I watched them being entrepreneurs and thinking outside the box.

Allison Kugel: By the way, there is a strong connection between financial empowerment, a belief in one’s future, and the desire to look after one’s health, which I am sure you know.

Mathew Knowles: Health is number one. Without that, you actually become a liability to everyone. You can’t be the best family member, you can’t be the best friend, without having good health. I’m sitting here today speaking to you because I understood early diagnosis and early detection, and I was able to find my cancer early at stage 1A. Not everyone has that opportunity. This is about early detection, knowledge, and understanding of health. Believe in faith, but also believe in science. Put them together; not one by itself.

Allison Kugel: Aside from the Flex for Checks initiative, in what other ways is the National Minority Health Association reaching out to communities of color to help people look out for their own health?

Mathew Knowles: All of the things we are talking about today. They are less than a year old and they have just gotten their funding, which takes a while to get. They are now ready and geared towards early detection and health information, especially in the Black and brown community. A lot of our challenges are just because we simply don’t know, and also the mental health that people don’t want to talk about, especially in the Black and brown community, and the effects of mental health, or the lack thereof, on our overall health.

Allison Kugel: Do you think cultural competency among healthcare providers is an important ingredient when it comes to healthcare, whether it is mental health, early detection screenings, or getting the COVID-19 vaccine?

Mathew Knowles: I think that falls into the entire gamut of society. If we were able to see more doctors and more nurses that look like us, if we were able to see more police that look like us in our communities; I think we can even take that to corporations. Yes, absolutely. This is my second year going to Harvard for the summers. I took this summer [course], Cultural Intelligence. We just don’t want to talk about the differences in our cultures. Black people are culturally different than white people. That is not saying one is right or one is wrong. That simply says that the way I might approach a problem could be different than the way you approach a problem, based on my culture and my background. I just think we need to understand cultural intelligence, understand how we are different, and accept that rather than thinking that everybody has to be the same. Well, no, we don’t have to be the same.

Allison Kugel: Let’s talk race versus socio-economic status, and healthcare. As a person moves up the economic ladder, do you think race is still a major factor in the healthcare someone receives?

Mathew Knowles: There is a bill that is about to come in the next six months in the House of Representatives from a California Congressman that is going to address just that, race in the medical system. Quantitative research with doctors and with hospitals makes it very clear that race does matter in terms of those going into emergency rooms, and who gets to get the diagnostics like the CT scans, the MRIs, and the extra care. Race does matter.

Allison Kugel: Even as you move up the economic ladder?

Mathew Knowles: I think it’s certainly reduced as you go up the economic ladder, because what happens is, as you go up the economic ladder, normally, your new knowledge base also goes up.As your knowledge base goes up, you begin to understand that this doctor who I looked up to as God, instead it’s the knowledge that you are going to see a physician and as a patient you have the right to say, “I want this procedure done,” or “I have the right to do that, because I’ve researched and I want you to perform that test or that procedure.” I think as you move up economically your knowledge progresses.